COVID-19–the highly contagious respiratory illness–has rapidly become a global pandemic, with countries closing borders, restricting domestic and international travel, closing businesses, and even enforcing national quarantines. While the top priority of every country is to treat the ill, develop a cure, and ultimately distribute a vaccine for the virus, the U.S. government is also taking action to address the economic crisis caused by the Coronavirus.

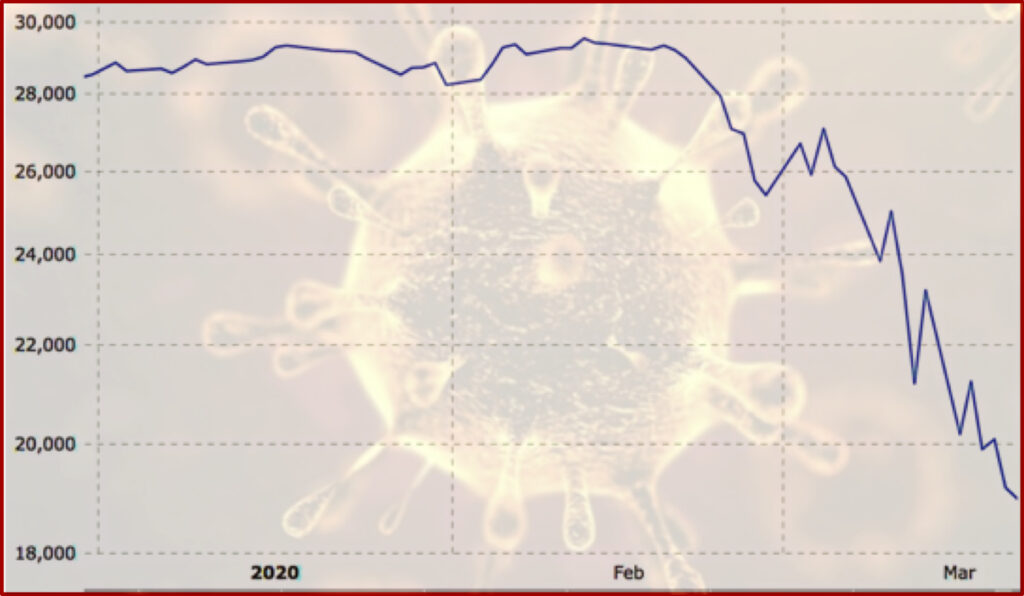

In a short period, the pandemic is already having a devastating effect on the U.S. economy. Jan Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs, has predicted an unprecedented 34% decrease in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the second quarter of 2020. Furthermore, between the period of February 23rd to March 23rd the Dow Jones Industrial Index dropped by more than 33%, a faster 30% decline than even during The Great Depression. Is there anything that U.S. policymakers can do to minimize the impact of the recession and stimulate an economic recovery?

The U.S. has a set of tools that it typically deploys during recessionary periods, mainly monetary and fiscal stimulus. Traditionally, the central bank combats economic downturns by lowering interest rates to encourage businesses and individuals to borrow money, spend, and invest. The Federal Reserve already aggressively utilized this tool when, on March 15th, it committed to lower the federal funds rate to between 0-0.25%, which it had not done since the financial crisis of 2008. Yet, once the markets opened the following day, it became obvious that this tactic was not going to work according to plan. On March 16th, The Dow dropped 3,000 points, the largest percentage decrease since 1987, signaling that lowering interest rates was not going to have the expected effect.

The U.S. government also often responds to a slowing economy with expansionary fiscal policy tactics. As recently as the Great Recession of 2008, former President Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act into law, designed to offer social security and unemployment benefits, cut taxes for middle and lower income citizens, and create jobs through massive infrastructure projects. This legislation served as an attempt to boost consumer confidence, putting money in the pockets of Americans, thereby encouraging consumer spending and spurring economic activity. The stimulus package that was just passed by Congress on March 27th reflects a similar approach to the ARRA.

It’s important to note that both monetary and fiscal stimulus represent demand-side solutions for demand-side economic problems. In the case of the current COVID-19 crisis however, these familiar tactics might prove ineffective, as the current economic crisis is as much a supply problem as it is a demand one. In The New York Times Daily podcast on Monday, March 16th, economic journalist Peter Goodman explained that “the traditional playbook can’t do much, if at all, about a supply shock. And what we have now is a supply shock,” referring to how the virus has disrupted the global supply chain and prevented thousands of businesses from manufacturing and stocking their products. Furthermore, the expected decrease in consumer spending due to the loss of jobs and uncertainty about the future, is being exacerbated by mandatory quarantining and social distancing rules, which legally prevent people from going out and spending on goods and services. So, while expansionary monetary and fiscal policy are expected to have some impact on the weakening economy, in reality this unique economic crisis may require new economic tools. Which brings us to Friday March 27th, when Congress passed a 2.2 trillion dollar stimulus package, the largest in U.S. history. An essential part of the stimulus program is direct cash payments to households, which will be critical to helping Americans survive this health and economic crisis. However, whether or not this initiative will actually stimulate the economy and pull our country out of a recession remains to be seen.