By: Edward Ding

December 18, 2020 was a particularly bad day for SMIC, China’s largest semiconductor manufacturer. The U.S. government blacklisted dozens of Chinese companies, including SMIC, and effectively restricted their purchase of advanced U.S. technology. SMIC, already behind foreign competitors in terms of chip technology, found its plans for catch-up innovation further complicated; its production processes were and continue to be significantly reliant on American tools, equipment, and components. The blacklist’s detrimental effect has yet to fade, but SMIC is likely turning to a different, domestically-oriented path to the technological frontier.

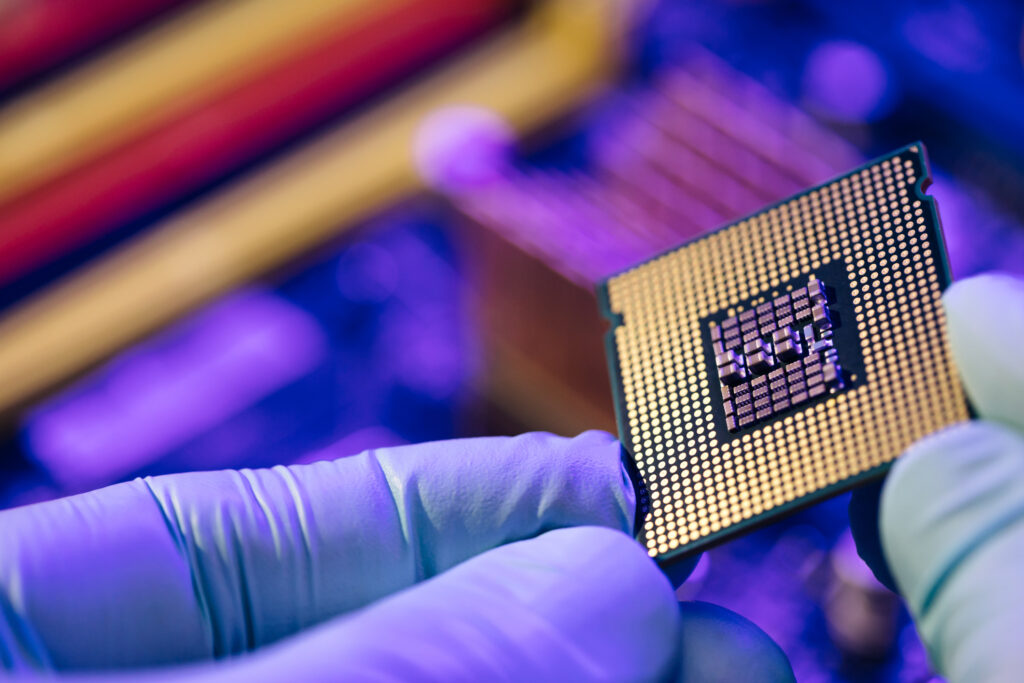

Semiconductors, also known as chips, are an essential part of virtually all modern electronics. Products ranging from smartphones and computers to electric vehicles and washing machines make use of semiconductors to process or store data. The chip industry is dominated by a handful of large companies, which can generally be split into three categories: those focused on manufacturing (foundries), those focused on design (fabless companies), and those involved in both (integrated device manufacturers, or IDMs). Two Asian firms, Taiwan’s TSMC and South Korea’s Samsung, are among the world’s largest and most advanced chip producers; TSMC specifically supplies the likes of Apple and Intel with its products and capabilities.

Compared to its competitors, SMIC is very much less advanced in its manufacturing. Semiconductor makers aim to make each generation of their products smaller in size than the last; chips are so tiny that their size is measured in nanometers, with cutting-edge processes achieving single digits. SMIC, however, is focused on legacy chips, meaning those using 28 nm processes or larger. In Q4 of 2021, the company reported over 60 percent of its revenue as being derived from chips using 55 nm technology or larger; its current smallest chip is 14 nm, which entered mass production at the end of 2019. Meanwhile, American IDM Intel is at 10 nm, with 7 nm to begin production this year, and TSMC has already begun trial production of 3 nm chips.

As a whole, SMIC is roughly four to five years behind the technological frontier, and catching up has only been made more difficult by the U.S. blacklist. With its access to vital technology imports restricted, SMIC will have trouble producing semiconductors using 10 nm processes or smaller. American pressure on the company isn’t likely to ease anytime soon, given the persistent geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February, U.S. authorities warned Chinese companies against defying the export sanctions placed on Russia; SMIC was singled out by name in this warning. So long as Sino-American relations remain frigid, the company will continue to face restrictions.

Despite these serious headwinds, SMIC may still find potential in its home market, where it generates most of its revenue. A vast majority of SMIC’s customers are based in mainland China and Hong Kong, which together represent over 60 percent of the world’s semiconductor consumption. Domestic demand has reportedly been strong in recent quarters, and the pandemic’s ubiquitous supply chain snarls have motivated many Chinese businesses to pivot towards local chip suppliers. The growing presence of government support has also been a boon to SMIC. Spurred by what it perceives as U.S. suppression of Chinese companies, the Chinese government has increasingly put emphasis on the self-reliance of domestic industry. Through state-owned enterprises and investment vehicles, the government has poured money into “strategic emerging industries”, aiming to wean them off of dependence on foreign technology. The Chinese government is already one of SMIC’s major investors, with state entities Datang Telecom Group and National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund being two of the company’s largest shareholders.

Financially, SMIC has seen rapid growth and steady profits. For 2021, the company reported a 39 percent year-over-year increase in revenue, with a 138 percent increase in net profit. In the short term, SMIC may also be able to benefit from the global semiconductor shortage, which has yet to show signs of abating. Notably, in many countries, the largest order backlogs are for legacy chips; many manufacturers have only invested sparingly in the production of these older processes. SMIC, as a major legacy producer, stands to benefit.

SMIC’s path forward is uncertain and not without obstacles, but it is by no means hopeless. Catch-up development will still take years, if not longer without U.S. technology. The company will no doubt continue to dominate in the Chinese market; whether or not it will succeed in gaining a real global presence depends on the persistence of U.S. pressure and the success of the Chinese government’s “self-reliance” campaign.