By: Trevor Jones

Drug use, especially the opioid crisis, is one of the most prominent public health issues in the United States today. According to drugabuse.gov, a government-run site detailing the data about drug abuse in the United States, over 47,000 people die every year due to opioid overdose. The same webpage also states that 1,700,000 American citizens suffer from prescription opioid-related substance abuse disorders, as well as 652,000 with a heroin use disorder. While there is potential for these latter two statistics to overlap, the magnitude of these numbers is still alarming. Not only have I seen the effects of substance abuse in my own life, but many of my new classmates that I have met over the last semester have had similar experiences in their friends, family, or someone they know. The Vanderbilt University Medical Center cites Tennessee as the state with the 15th most drug overdose deaths nationwide, showing how it affects our college community in addition to many people’s home communities. Substance abuse runs deep in this country, and it seeps into everyone’s community, however insulated they might be from traumatizing experiences. Moreover, the economic fallout of the drug epidemic is significant: a study by the University of Pennsylvania Health System found that the combined toll of drugs and alcohol on the public healthcare industry, on crime, an imprisoned workforce, treatment and car insurance costs is around $562 billion. Yes, these statistics are undoubtedly inflated with the addition of alcohol into the mix, but that does not change the need to act.

So, how do we combat this? What steps can we take to fight this epidemic? Well, so far, the confrontation of the opioid epidemic has been predictable. Federal lawmakers demand accountability from pharmaceutical companies and greater restrictions to obtain opioids in the Opioid Crisis Accountability Act of 2019. They also allocate funding to the Center for Disease Control, the Department of Health and Human Services and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, or SAMHSA. VUMC’s site mentions a “TN Together” Public Chapter that aims to redefine the requirements to get an opioid prescription. While all of these are good steps to take on the surface, what if we re-thought this epidemic and confronted it in a new way?

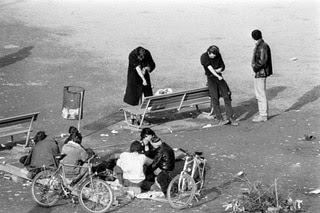

The European country of Switzerland came across a similar problem in their country in the 1980s. Platzspitz Park, a beautiful public park in the city of downtown Zurich, came to be known as “Needle Park” as it was overrun with thousands of heroin users. The surrounding area began to have more and more problems: crime rates, HIV transmission rates, and drug overdose deaths all ran higher than usual. To fight this, the Swiss government embraced a “four pillars” policy, as cited by an article from the North Carolina Health News. This article goes in depth about these pillars, which are harm reduction, treatment, prevention, and (law enforcement) repression.

Harm reduction means reducing heroin consumption in any way possible; the Swiss government provided supervised rooms to use drugs, strategically placed near high-drug use areas, so that those who are addicted would be at a lower risk of an overdose since they are being supervised by a qualified medical professional. The government also provided clean needles and regulated heroin to citizens so that they would help cut transmission rates of diseases and confirm the safe origin of said heroin. For treatment, the barriers to be treated for substance abuse are unbelievably low, making it easy for someone to walk into a clinic and receive treatment.

Swiss treatment includes the use of an opioid substitution program that takes the user off more dangerous opioids and transitions them to a similar — yet less lethal — drug. Prevention of diseases, crime, and death is achieved by the other goals in a positive feedback loop. When drug users are off the street and using clean needles, the danger associated with using these drugs, especially illegally, is significantly reduced. To focus on prevention, Switzerland focused on their other goals to help improve preventing substance abuse. Repression by law enforcement utilizes an approach to focus on dealers rather than consumers. The Swiss prosecute 75% less opioid-related crimes in 2017 than in 1993, according to the same NC Health News article, being at 5,000 today down from 20,000.

What were the results of the “four pillars” approach? Most importantly, a significant rise in accessibility to treatment, across the country of Switzerland. A 64% decrease in opioid-related deaths in 2017, an 83% reduction in positive HIV test results, a 98% reduction in theft, and an overall decrease in crime.

There are reasons why this would be tough to implement in the United States, however. Widely differing regions mean a different level of necessity for each state, and a different economic impact that funding this solution would have on certain parts of the country, depending on how harshly the epidemic has affected different areas. The United States would likely struggle to secure funding for this project, especially given the unique way it goes about being a solution to substance abuse.

Nonetheless, alleviating this crisis by supporting substance abusers, not vilifying them, would not only be a leap for the quality of life of United States citizens, but it would improve our economic well being as well. Using this solution helps save lives, money, and make our country and world a safer place. When thinking about this, it is encouraging to see success with thinking outside the box, since the solution to this problem is not straightforward.